Was enjoying a quiet Sunday morning reading the Tampa Bay Times when I came across this phrase in a Marc Topkin analysis of Ha-Seong Kim’s two-year, $29 million deal with the Rays:

“… the second largest the Rays ever have given a free-agent position player, behind Greg Vaughn’s $34 million, four-year contract in December 1999 … ”

First thought, that can’t be true.

(But of course it was true. Never doubt Topkin.)

Second thought, that can’t be healthy.

Sure, we all whine about the Rays having a low payroll. And fans everywhere bemoan how the biggest stars always seem to land in the biggest markets. But revenue disparity is becoming so commonplace — and accepted — it’s threatening to ruin the integrity of the game.

In the franchise’s 27-year history, the Rays have signed just one player — Wander Franco — to a contract with a total value of $125 million or more. The Dodgers have signed seven of those deals just in the last four years.

In essence, the Dodgers have attempted to corner the market on hope.

That’s not an insult or an accusation, by the way. The Los Angeles front office has done exactly what a responsible big-market team should do. They’ve spent money, rather strategically, to build the best roster in the majors.

And whether the Dodgers win the World Series is not the issue. We’ve been reminded, time and again, that baseball’s postseason can be a crapshoot. The real concern is that we’re getting to a point where too many teams begin every season without much hope of reaching the playoffs.

That’s not just unfortunate, it’s potentially calamitous.

When hope is squashed before the first pitch is thrown, you basically have a 162-game schedule of exhibitions. You’re asking fans to commit their devotion, their time and their wallets to a team that has no prayer of competing for a playoff spot.

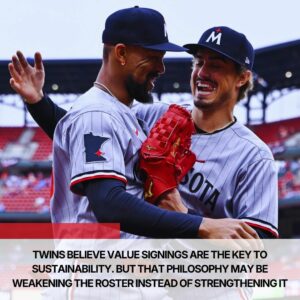

Whether you view it as fortunate or not, the Rays inadvertently have contributed to the status quo by succeeding despite their revenue issues. The Rays have been in the bottom third of MLB payroll in each of the last 17 years and have reached the postseason nine times for a success rate of 53%. Every other team in the bottom third has a success rate of 18%.

Tampa Bay’s onfield success has allowed baseball officials to point at the Rays and say, “See, it can be done.”

But that’s ignoring the overwhelming evidence that it’s easier to reach the postseason with a bigger payroll.

Now, of course, you could place the blame at the ledger of owners who do not overspend on salaries. That certainly plays a role.

Stay updated on Tampa Bay’s sports scene

Subscribe to our free Sports Today newsletter

In Tampa Bay’s case, the numbers strongly suggest it’s a market issue and not an ownership problem. The Rays have the third-best record in baseball since 2008 and are wallowing near the bottom in total attendance.

When the teams with payrolls above $270 million (Dodgers, Yankees, Mets, Phillies) are in some of the largest markets and teams with payrolls below $75 million (Rays, Marlins, Pirates) are in low-revenue markets, it’s not hard to connect the dots.

And that’s a flaw in the system.

It’s not the fault of the Dodgers. It’s not the fault of the commissioner. It’s not the fault of the fans. It’s just the evolution of the game. For close to 100 years, owners had all the power and used it to artificially keep salaries low. Beginning with the influence of the players union and free agency in the 1970s, the power structure shifted and salaries soared.

I’m not suggesting salaries need to be lower, but competitive sports work best when they’re … well, competitive.

And the recent spending spree by the Dodgers might just be the tipping point for change. A new collective bargaining agreement needs to be reached before the 2027 season, and there’s a decent chance enough owners will want to see substantive changes to ensure a level playing field.

Does that mean a strike or a lockout is likely before 2027? Yeah, there’s probably a pretty decent chance and that would stink.

On the other hand, would you prefer a sport where all the best players are destined for the same wealthy teams every year?